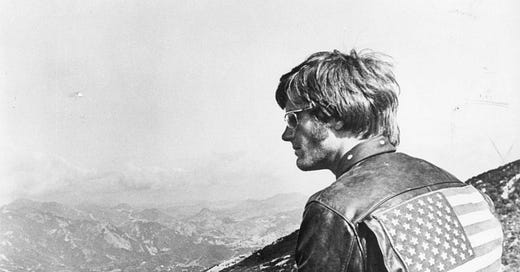

And I wave goodbye to America

And smile hello to the world

Read part 1, “Why Don’t We Sing This Song All Together,” here:

Many songs evoke the counterculture 60s, famously for those who’ve learned of the era through historical lore, more personally for those who lived through them. For me, even as I was relishing and surviving those years, none captured their sweet promise and foolish bluster more poignantly than Tim Buckley and Larry Becket’s Goodbye and Hello, with its marriage of folk lyricism to Kurt Weill, Weimar theatricality.

O the new children dance ------ I am young

All around the balloons ------ I will live

Swaying by chance ------ I am strong

To the breeze from the moon ------ I can give

Painting the sky ------ You the strange

With the colors of sun ------ Seed of day

Freely they fly ------ Feel the change

As all become one ------ Know the Way Know the Way

Did Arnie and I feel like new children seated in the dirt listening to…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

![California Dreamin’ [From the Archives]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pUKn!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc303a86e-f8ac-49d4-9201-64f34b772ab6_500x333.webp)