Free to all this Monday, “California Dreamin’,” in two parts drawn from Homo Vitruvius’s older-than-three-months, paywalled archives — with part II to follow Thursday next week — comes from only the second full month of the Substack’s life, when planet Vitruvius rotated still but a solar stripling smoldering from its creation. It tells the story of my first travels away from New York on my own, at the age of 17 with my best friend, hitchhiking up the coast of California during the culturally emblematic summer of Woodstock and of my journey’s traumatic aftermath. Its chronology follows by two summers the vision I offer in “Hot Town (Summer 1967).”

This coming Thursday, I will post the first entry in the new monthly two-part series A Reader’s Review, with the second part to follow next Monday.

Ann-Margaret was dancing down the middle of Sepulveda Boulevard.

We were watching her from an overpass above. We were 17 and 19, and we had just walked out of Los Angeles International Airport in August of 1969 lugging old, battered suitcases banging against our thighs. The earlier part of the summer had been devoted to earning the expense of this first ever trip away from home on our own — a three-week odyssey up the coast of hippie California. Arnie had labored as a post office sorter, I as a desk clerk at the New York State Insurance Fund, where my mother was a senior underwriter. But there was no allowance in the budget for taxis, out of airports or to anywhere. So we walked out. Suitcases in hand and twitching, exuberant noses to the air, we crossed over Sepulveda toward what was called Century Boulevard, we looked down from the overpass — and we saw her: Ann-Margaret, Hollywood sex kitten, strutting down the street just outside LAX the very hour we arrived.

Hooray for Hollywood.

Of course, there were cameras on cranes gliding along beside her, filming her. That was Hollywood, too.

A magical welcome it was for two New York hippie boys, in-the-know, who knew so little.

Not that we two counter-cultured teens were very much fans of Ann-Margaret, beyond the obvious allure for two hormonally raging hetero boys. We hadn’t traveled from our New York, Rockaway Beach and East Village hangouts all the way to California — “promised land of my people” I would call it that fall in a senior-year creative writing class essay — to ogle the last gasp of old-line Hollywood’s old-time minor star creation. We had come, rather, to make pilgrimage, to the Sunset Strip, the Pacific Coast Highway, Santa Barbara, Big Sur, Berkeley, Haight-Ashbury, Golden Gate Park. We were in thrall to experience.

In those days, my name was Arnie. My friend, the older and shorter of we two, the redhead — he was Arnie, too. We were two Arnies, and we arrived in Los Angeles the first week of a month in which the world would famously contradict itself. The world, it need be said, contradicts itself all the time, every day, even every moment — consider the oscillations of the sub-atomic neutral B meson particle, for instance — but not always so noticeably, and even when the spinning globe shouts for our attention, to please themselves people choose what they wish to hear, and, even then, remember. So people picked and chose, it was all a fearful muddle in the Age of Aquarius, and by August of 1969, Joan Didion had lost the thread of the story. Arnie and I, ourselves keenly attuned in more adolescent fashion to the tenor of the times, had traveled from one coast to the other also with the plan to hear Blind Faith one more time sing “Can’t Find My Way Home” — a not uncommon way for a seventeen-year-old already to feel, but made more disorienting by our sense of being culturally as well as personally adrift.

We crashed that first California night in Richard Nixon’s conservative, Christian birthplace of Whittier, the kind of town in the U.S. of that time that youngsters like the two Arnies felt themselves scorned as “the people our parents warned us against.” We’d been led there by the acid-head version of a letter of introduction from our friend Jerry, third in our troika, who’d made his California pilgrimage before us. Scrawled in pencil on white copy paper, it listed contacts from Los Angeles to Berkely, with the request that Arnie and I be offered shelter and “refreshments for the mind.” Despite the cultural tensions roiling cities and bedroom communities across the nation, even in Whittier we found a backyard of teens in transit. Far from anywhere we actually wanted to be, in the morning, while the resident mom and dad attended Sunday church service, Arnie and I set out on the road again, in eight hours of nearly futile thumb waving, to escape that sun-blanched and hostile terrain. We finally caught a ride and managed, absent cell phone and GPS, to meet up with my older brother, Jeff, 22, already in the Golden State on his own, better financed odyssey, of California-girls fornication up the Pacific coast.

Jeff had taken a motel room on the Sunset Strip, at the very center of the action, with a door that opened directly onto the street. Arnie and I shared the second bed. In the summer of 1969, the Sunset Strip throbbed and hummed with a nervous edge like a cross between a Silk Road bazaar and the canteen in Star Wars. Freaks abounded, hair flags flying, a foreignness of intention hanging in the air around every familiar transaction. Freaks hung on corners, roamed the streets, crossed them back and forth amid the stream of cars. They were dirty freaks, homeless freaks, drug-dealing freaks, and deal-making freaks, with sleek and slender, scene-making rock-club freaks among them, the wandering of spirit and the beautiful of body, male and female alike, adorning the storefronts and bejeweled in their exotic selfhood. Amidst them all, fiery and concentrated in full-throated declaration, Arthur Blessitt pronounced the word of God and hailed the Lord’s return to the deaf ears of all but the most desperate and lost. The atheist Arnie (the other one) debated him. This Arnie, shoeless and shirtless but for the thigh-length Mexican vest I wore during those years like a uniform beneath my long wavy hair and crab-grass beard, was snatched up by the LAPD mid-street, jaywalking between sidewalks, and, unable to produce identification, ticketed for vagrancy.

I made a certain impression. The world made daily impressions on me. Deep impressions. Overwhelming and fearful impressions. I tried to make an impression back, to hold the world back. But it was a lie. I walked the streets an insecure teen-aged boy, hungry for experience and afraid of the world, with the world spinning out of control all around me.

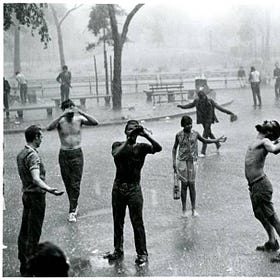

Joan Didion felt it too. It was in the air. Deliverance and danger dancing as a pair, naked torsos and wild flung heads flailing together in an open field of change.

By that time, Arnie and I had been acid heads for about a year. We loved our hallucinations, our swirling colors and intimations of ineffable truths that dissolved into the diffusions of forgetfulness. But since everything was already speeded up with youth by then, older brother Jeff, falling behind, had not himself yet dropped acid. He was doing downers. One night, late, Arnie and I already asleep in bed, Jeff stumbled off the street into the room and took down the bed lamp reaching for the air before dropping to the mattress unconscious. Then, in those very early morning hours later, back to sleep, the memories of the previous phantasmagorical Saturday evening still shaping our visions, we woke again to a man roaming up and down the Strip, screaming so everyone, including he himself, could know, “I’m not crazy! I’m not crazy!” Daylight come, and the three of us roused, Arnie and I ventured out onto the street to retrieve that day’s Los Angeles Times from the corner vending machine. We saw at once, standing in the metaphorical shadow of the Hollywood Hills, the right-side headline: “Ritualistic Killings: Sharon Tate, Four Others Murdered.”

It would be some time before the killers’ identities were known, and more murders would follow, but that such events had occurred seemed awfully unsurprising, if terribly unsettling. After all, “Rape, murder” was “just a shot away,” the devil-channeling Rolling Stones would tell us on Let It Bleed just months later. But the bitter, piggish street slang for police mixed in with the name of a Beatles song, written on a wall in human blood?

Helter skelter?

Yeah, it was.

I chose at the time to dress and look like a hippie because one of the ways you become something in the world, in your life, whatever it is, is to try to appear as what you want to be. Every dress-for-success, business-world aspirant knows that. People of all ages try to look like some internalized image of themselves, though teens of every generation do it with a special poignancy. By 1969, the naivete of this notion, and the look it produced in nonconformist uniformity (and the cynicism driving its commercial capitalization) had devolved, in actuality, into people from ages 15 to nearly 50 needing to be instructed daily, as if it was the delivered wisdom of the ages channeled through the counterculture like the lessons of elementary school. Don’t break into concert venues without paying for the ticket, stage managers would implore. (Don’t break into concert venues.) Don’t charge the stage. Don’t spike people’s Boone’s Farm and Wild Turkey with unknown drugs they don’t know they’re taking. (It’s not cool.) Don’t cheat people with pot lookalikes that aren’t pot. (Really not cool.) Treat people, yeah, the way you want to be treated yourself. That was a new one.

What a revolution, got to revolution.

And that long-haired, bearded guy at the party who looks like one serious kind of wild hippie freak — man, he’s got a far-out rap — may not actually be all about peace and love like you presumed. He might be a hitter. He might be Charles Manson.

Shit. He was.

But Arnie and I were kids. There were kids all around us, many of them actually kids, and though the two of us were freaked out, the whole world, in truth, was freaked out, everywhere you looked, and we had lives to live and adventures to pursue, and a next stop in Santa Barbara, on the way north, to see Blind Faith for the second time that year, since the first time at Madison Square Garden in New York.

On the morning of August 16, 1969, then, with Woodstock underway back in our home New York environs, Jeff drove his younger brother and his younger brother’s best friend to the Pacific Ocean in a rental car, to the intersection of Chautauqua Boulevard and the Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica to begin hitch hiking their way northward. We would meet again in Berkeley at our northern end.

Arnie and I held out our thumbs again. If the Sunset Strip was like a Silk Road bazaar, the PCH was the Silk Road itself. Beside an ocean of sun-speckled waters, along a mountainous winding coast, within a delirium of salt-sea air and sea haze hanging over the cliffs, young people were traveling up and down the highway, in and among an endless train of cars, with surfboards under arms and packs on their backs, like donkeys climbing up into the mountain passes of Persia. If they weren’t actually carrying the wares of cultural exchange, they bore instead the wonders of cultural change, and yes, it was a wondrous time to be alive, to be young and free and reckless and bold and on the road to somewhere, including the rest of your life.

A station wagon pulled to a late stop, just passed us. Already jammed with teenage bodies, there was always room for more. Arnie and I crawled our way in over the others. A joint passed into our hands as the driver shifted into gear. The music pumped up louder as the road sped by beneath us. From the Rolling Stones’ psychedelic Their Satanic Majesty’s Request album, we heard, “Why don’t we sing this song all together,” everyone in the car joining in to sing:

. . . Open our heads let the pictures come

And if we close all our eyes together

Then we will see where we all come from.

AJA

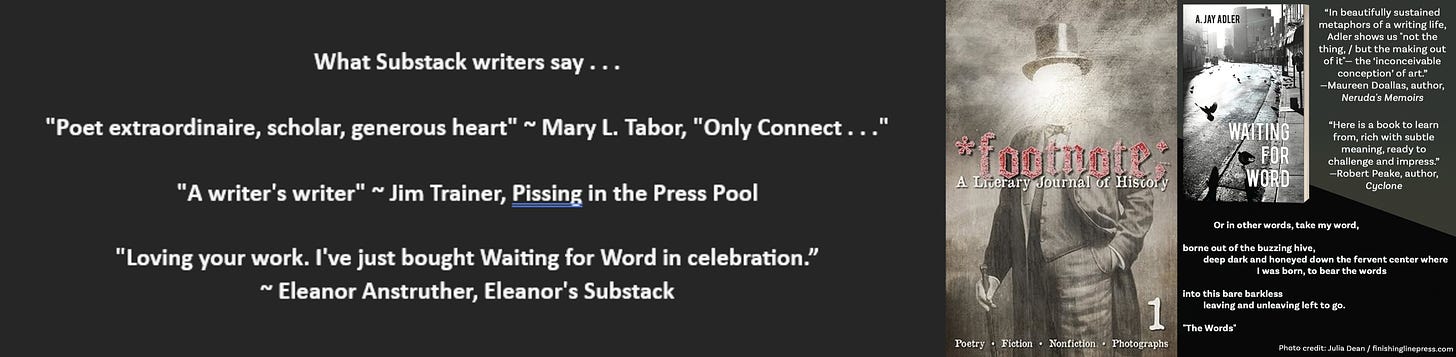

Writing that dares, thinking that delves deep, emotional explorations that range. Become a paid subscriber of Homo Vitruvius today. You’ll get access to the full archive, Recs & Revs posts, the Magellanic Diaries, Extraordinary Ordinary People, and A Reader’s Review. You’ll also have access to a free digital download of Waiting for Word and the opportunity to purchase signed hard copies of Waiting for Word and Footnote.

Poet. Storyteller. Dramatist. Essayist. Artificer.

“Not just words about the ideas but the words themselves.”

Oh wow. The 60s are my favourite era, although I was born right at the end. To have been in the middle of it all must have been mind blowing. You really know how to hold us (readers) in your story.

Same Vintage....well written and like you still weaving my way through "the Danger and Deliverance" ^..^