A Lark

a form of memory

Your likes, comments, shares, and recommendations, and your free and paid subscriptions help gain attention for my writing and aid the mission to offer a renascent light against the darkness: art, information, culture, and ideas for a free, tolerant, and democratic people. If you read by email, all you need do is click the title to access the Homo Vitruvius site to offer a like or comment. Even the modest monthly subscription rate of $2 gains access to the full archive.

We dropped the doses of Purple Owsley at Erik and Lance’s house. Then we headed out to the beach in a golden late afternoon of early fall. The descending sun lit us along our way through tree lined Belle Harbor streets. We talked. We joked. We leaped into the air in happy anticipation of the acid coming on. In that in between hour, the transition from uncertain light to unyielding darkness, our voices echoed. We were ten — Eric, Lance, Jerry, Arnie, Michael, Jeremy, Dana, Alan, Crank, and you. Crank was a funny name, not what his mother gave him. Crank was called crank because every car has a crankshaft and some cars are a lot bigger than others. He wore a ripped stovepipe hat above a weathered. leather vest that hung loose over a long naked torso. You wore your own vest, a thigh-length Mexican over a hairless chest. Jerry led the way.

As we neared a pathway to the beach, off a residential street, we gathered small twigs and fallen branches, then dried driftwood on the sand. Scattering with enthusiasm over the cooling grains, we then gathered back around to dig the fire pit where Jerry and Eric constructed the teepee. Lance worked to light the fire. Soon, the day steadily leaving us, the fire began to crackle and blaze.

The off-peninsula swarms gone with summer, the sunbathers no longer lingering late as the evenings chilled, we were alone in both directions. Autumn waves, churning up from the Caribbean, began to crash as the ocean receded from the shore. They curled over each other, dragging with them the brown muddy bottom they made of the once dry sand. The wind whistled a little, and there was the hollowness of endings to be felt if you were the kind of person inclined to turn sad, which you were. Day was done.

When you are seventeen years old, almost every experience you have is new. The newness is like waves crashing over you. Forget to gulp a mouthful of air in preparation, neglect to curl your body and protect your head — or to leap, boldly, over the crest — and you get buffeted and tumbled around. That’s part of the newness, too — the tumbling.

It was new a few weeks earlier, just a street or two away along the beach, when you walked out into the darkness alone with Kerry McCorkle. Jerry had said, if you want your first blowjob, I hear Kerry McCorkle gives them. You wanted it, but you weren’t going to do anything about it. Then one evening, not long after, she was at a party with you and she was talking with you. You had never seen her before. Then you were walking out in the darkness and she was laying you down in the sand. It’s okay, baby, she said. She was stroking your cheek and pulling down your pants. I’ll take care of you. The moonlight caught her face against the dark sky. She seemed sweet, almost innocent. You’d thought she’d be rough. You want to watch, baby? It’s okay. You can watch.

You never saw her again after that night.

Maybe it was because of that night — who can account for these things — that a few nights later, you took the motorcycle ride with Jerry.

Jerry and Arnie were two years older than you, and they were your best friends. Jerry was very tall, with a big, fun, dominating personality everyone gathered around, the kind of guy that you had always ended up friends with, weathered and wizened scouts, compared to you, into the wilderness of your fear, showing you the way, teaching you the landscape. Jerry was smart, too, like all your motley gang of freaks, daring and reckless. He had other groups of friends, older, around the city, who connected him to experience way beyond his years, some of which became your experiences. How’d he end up in charge of security at the Fillmore East, where every major rock band in the world played? Who knew, but he got you a job on the crew there. Luckily, you were at the side, stage door the night the Hell’s Angels brawled at the front door.

You’d all been smoking weed on a top stairway landing of the beach apartment buildings you lived in, when it finally got late, around midnight. With nothing to do, everyone was heading home.

You going home too? Jerry asked.

Why? You want to do something?

Ed Carlin just got a new apartment in the Bronx. You want to pay him a surprise visit?

Now? On the fucking A Train? It’ll take four hours.

You know I bought a motorcycle. A Triumph. Only five hundred dollars. It’s in excellent condition.

Wow. Really? How’d you get such a good deal?

It has no brakes.

And you want to ride it to the Bronx? Are you serious? It must be twenty-five miles!

I’ve been riding it all week. It’s no problem. I just downshift and drag my feet. With two sets of feet, it’ll be even easier.

You thought about it. You couldn’t believe you were thinking about it. You couldn’t believe you were going to do this.

You were going to do this.

You really suck, you said, blaming Jerry for the temptation.

Yeah, but I suck a big one.

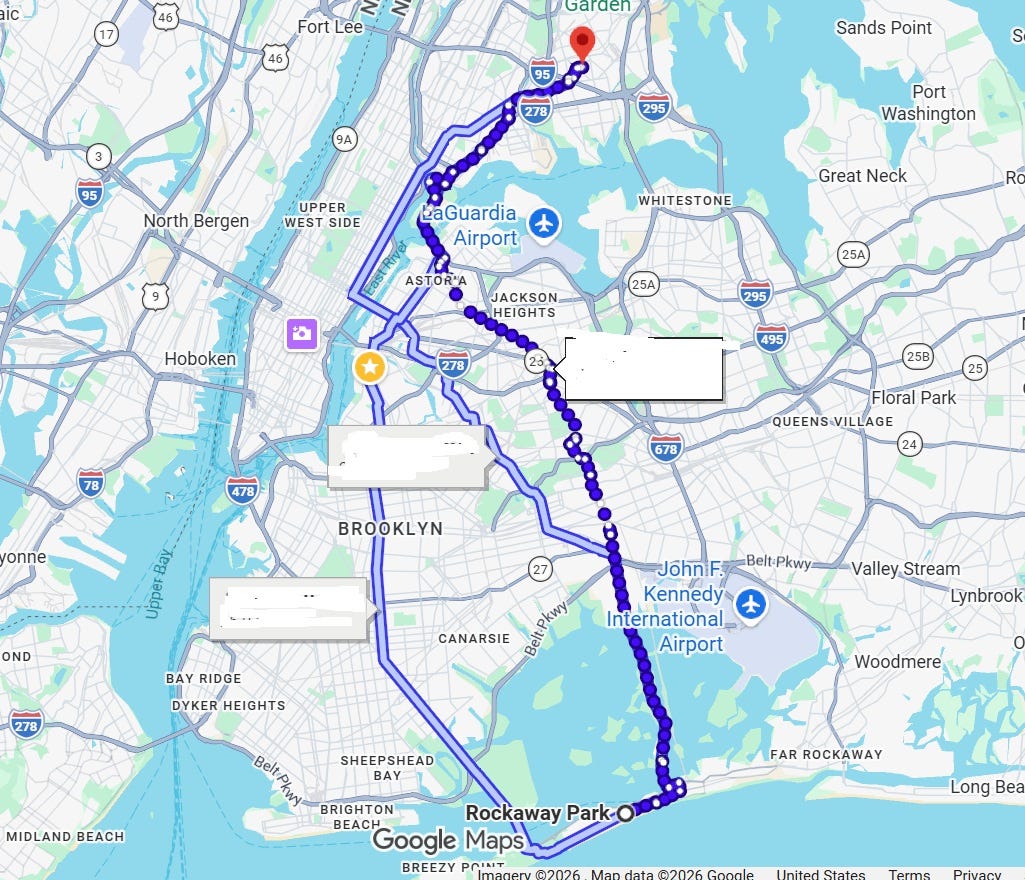

You rode, then, holding Jerry’s waist from behind, the twenty-five miles to Ed Carlin’s place, traversed the Cross Bay Bridge over Jamaica Bay — night flights from JFK airport ascending overhead — to the Van Wyck Expressway, to the Grand Central Parkway, up over the Triborough Bridge and the East River, down the long ramp into the Bronx, with Jerry downshifting expertly, maintaining your distance among the thousands of vehicles that crosshatched the life of New York City on a Saturday night, both of you dragging your new Frye Boots hard over New York roadway to slow the bike further in the speeding and slowing and leaning turns that marked your journey.

When you reached the house where Ed Carlin was renting a room, at 3 in the morning, Jerry led you on a climb onto the roof of the garage, from where he jimmied the window to enter. He crouched beside Ed asleep in his bed and shook him, gobsmacked, awake.

What the fuck?

The three of you smoked some dope laughing, over the adventure. You examined the holes worn clear through in the soles of your new boots, showed them to Jerry, who peered, then, at his.

Cheaper than new brakes, he said with a Jerry shrug.

Soon, Jerry decided he’d stay through the day, so at first light, without any sleep, you took the A Train two hours back to Rockaway.

It was Jerry who got you drunk for the first time, at a party welcoming Mike Berezin’s brother home from Vietnam, then found you slid down to the ground at the base of the pillar you’d tried to hold on to. He got you and Arnie all your best pot. He introduced you to acid.

The gang of freaks to which you belonged were an intellectual bunch, but the kind a high school would categorize as under achievers. None of you by this point were going to college out of town or earning scholarships or making your mothers proud. You were friends with all the people who would and did those things. You took the same electives from the same best teachers. You were just too busy getting high and encountering the reality of experience, you'd learned James Joyce had so well put it. But you disdained downer dopes and space heads who sat zonked out and uttering inanities on acid at parties. LSD was exploration, an expansion of the mind in pursuit of a rollicking good time, not a stupid dulling of the personality. You were all voyagers into unknown lands, and you were proud to take your own controls. Drive a car while peaking. Sit at the kitchen table with your parents, tripping out of your mind, and carry on a conversation so well they would have no idea. Lie back on the floor, eyes open, and let the field of your vision fill with a swirling kaleidoscope of colors, sit up quickly as Jerry’s warring mother, Sadie, entered the room, push the empty bottle of mescal quickly under the bed, shake the kaleidoscope out of your head and smile.

Why, hello, Mrs. Cleaver. And how are you this fine night?

For fifteen minutes, you all engaged the best talk you’d ever had with Sadie, a mature, adult conversation with the fiercest mother of them all, your shrillest foe. Then she rose to leave in apparent satisfaction, pleased by a rare, normal conversation with her son and his two mangy friends. Her hand on the other side of the door to close it, she turned for one last peer inside her son’s sanctum of insurrection.

It smells like a fucking distillery in here!

And you howled with laughter at the closing door.

Now you were tripping again, on the beach, for the acid had come on, and Jerry was leaning forward in the sand, from his knees, close up, staring into your face.

You are fucking wasted, he declared.

Nothing wasted, nothing gained, you smiled back beatifically.

He grabbed both your cheeks, pinched and shook them. Boychick!

Acid come on? Arnie inquired from beside you.

God is in his heaven, you said.

All’s right with the world, said Arnie.

Everyone into the water! It’s skinny-dipping time!

Clothes flew from your bodies onto the sand in the full darkness now of night. You ran to the shoreline, where ocean was barely distinguishable from beach, less so from sky, the broken white lines of foam across the tops of running waves, again at the bottom of the breaks, the only clear markers of what was what. Bodies flew across the sky, dolphins arcing over the cresting waves, porpoises plunging into the bracing cold. You opened your eyes underwater engulfed in a marbled universe of blue-black ocean scored and circled with pulsing color forms. You hung suspended and stared, struck dumb in wonder. Finally, your lungs began to give way, and you broke the surface into air.

Holy fucking shit! you hollered.

Dana shot up out of the water nearby. Holy fucking shit!

Everyone was crying out.

Far fucking out! Alan yelled, turning in a circle to find the barely visible faces shouting all around him.

Fucking incredible! Did you see that? Jeremy called to him.

You lifted your head to the starry night, closed your eyes and opened them. It’s all the same, you said.

It is all the same. Alan said, circling your head with his arm and kissing it. All is one. Blessed be. He submerged himself again. One by one, they all did. You did.

You slept that night curled on the beach under the blankets you had carried, close to the fire that was out by morning. When you awoke in that morning, lying sideways in the sand, eyes opened to the ocean, you saw the first of the light break in the east, the earth dawning again in creation, with a pale primeval cast thrown over the ocean waters and the quiet slap of surf drawing back in the low tide. Gulls dipped and cawed over the breaks in the world’s first music. Every day it was like this, you thought. Every day the earth was born again in this glory.

This world. This world.

There were no words.

No — there were words. There were. You were searching for them. You would find them.

You wanted to swallow it.

You gathered yourselves to leave, lingering slow in the long come down, quiet and wordlessly philosophical. You would stop at the grocery for what you needed to make breakfast at Eric and Lance’s, their parents still away. You were wet still, your bodies spotted with clumps of damp sand, which clung, too, with seaweed, to your long, stringy, uncombed ocean hair and between the toes of your shoeless feet, your clothes creased and clinging to you.

You were freaks, all right, not hippies, who were already buried. People considered you freaks, so you would proudly be freaks. Nothing was yours to be accepted without thought, no convention of social arrangement, no law of living. Nothing unconsidered. Your purpose held, like Tennyson’s bold Ulysses, of whom you’d read in Mr. Fields’ class, “To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths / Of all the western stars” — “To follow knowledge like a sinking star, / Beyond the bound of utmost thought.”

That day, though, you were stragglers through residential streets early on a Sunday morning.

Up ahead, in counterpoint, an extended family of church goers in their Sunday church best, from children to elders, walked in your direction toward the church you were just then passing. Jerry, at the lead, with Eric, you and Arnie, passed the word quickly back. Give them a proper good morning.

So you did. Good morning, you said, nodding to their frozen glances. Good morning, you smiled. Good morning to you. Everyone polite and serious as if nothing were amiss, as if you didn’t look a gang of filthy hippie hooligans. All the way back to Crank in the rear, tall and gangly, loping beside the well-kept lawns like a derelict Abe Lincoln, who tipped his shabby stovepipe.

Top o’ the mornin’, he said.

At this, you held it as long as you could, until probably the good family had turned up the walkway to worship, when your laughter broke out, finally uncontainable in its delight, surely heard at the steps up and through the church door.

Life was a lark for a little while longer.

AJA

🖊️ Read my Daily Notes on Culture and the World: ➙ 𝓝𝓞𝓣𝓔S 🖊️

Homo Vitruvius and American Samizdat serve as my weekly open house, a salon in which I offer for your view some of my creative writing and intellectual exploration. HV persists as my original and primary Substack of these offerings; AS arose in resistance to Trumpism and in defense of Enlightenment liberalism. From memoir and poetry to fiction and drama, mostly in HV, to history and political philosophy, predominantly in AS, you will find them across the two stacks, which may be subscribed jointly or singly in Manage Subscription.

Poet. Storyteller. Dramatist. Essayist. Artificer.

How does anyone with a shred of curiosity or daring get out of adolescence alive? You took me back to the wild longing of those years. I was somewhere different on the map, yet fundamentally the same. Far fucking out.

I remember wanting to be David Bowie back then.

But now that he's dead, I guess I'm glad I'm not.