Homo Vitruvius and American Samizdat serve as homes for my weekly creative writing and intellectual exploration. HV persists as my original and primary Substack in these pursuits; AS arose in resistance to Trumpism and is dedicated to its defeat. From memoir and poetry to fiction and drama, mostly in HV, to history and political philosophy, predominantly in AS, you will find it here, integrated across the two stacks through a creative and intellectual sensibility I hope you will find invigorating. The stacks may be subscribed jointly or singly in Manage Subscription.

Your support for my writing on these two stacks lifts me up. Your readership and your likes, your comments, shares, and recommendations, and your free and paid subscriptions enable me in the creative project of my writing life and in my mission to offer a renascent light against the darkness: art, information, culture, and ideas for a free, tolerant, and democratic people. Thank you for your interest and support.

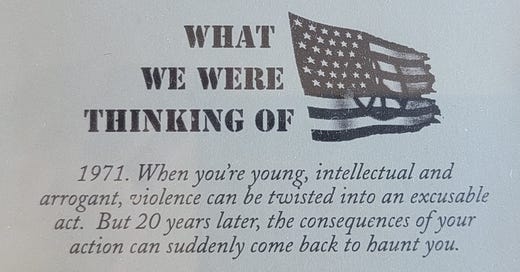

Next week, I begin serialized weekly publication of my play What We Were Thinking Of, in thirteen parts. Part I is entitled “The Words and the Things We Do.”

I am serializing What We Were Thinking Of on Homo Vitruvius for two reasons. One is that I want it to be read and known, and I have no particular reason to seek its publication off Substack rather than on, where it can more easily draw readers. Plays are not, however, after all, written to be read. They are meant to be staged and performed, and that, too, is what I hope for, my second reason for publishing here and now. I am seeking production and reading opportunities for the play, staged or not. Any and all interested theatrical parties are welcome to contact me. If you are an actor, director, producer, dramaturg, fellow writer, stage manager or any other theater person who forms an interest while reading and believes you can assemble the personnel at any scale to stage or read the play publicly, I would like to talk. Let’s explore. Let’s think it through. Let’s do that thing. Read on.

By the mid-1990s, I was living in Los Angeles. I had traveled there often since my first visit in 1969, during the summer of Woodstock and the Manson murders. During a visit in mid 70s, staying for a while with my brother, Jeff, in Malibu, I had shopped around the second of my, thus far, two screenplays.

In the Golden Age of Hollywood, screenwriters were usually under contract with one of the studios. But with the demise of the studio system and the rise of the New Hollywood in the late 1960s, the spec screenplay — a screenplay written speculatively by an independent writer and shopped to agents and producers — had begun to play a role in American filmmaking. The 1990s had brought not only me to Los Angeles but also the spec screenplay boom to Hollywood. Stories abounded of spec scripts — sometimes first sales – receiving payouts in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, occasionally a million or more. Hollywood had always been a lure for dreamers — now, in numbers greater than ever before, that included screenwriters, too.

I had stopped writing screenplays in the 70s, after a third, unfinished script. For a while at the City College of New York, I had been not an English major or a philosophy major but a film major. In those days, having grown up on films just as much as I had stories and novels, I wanted to make films just as much as I wanted to write. I had watched them on TV from my stomach on the living room floor as a child. I studied them in film classes at CCNY. I made a second home in what were then more than a score of art and repertory film houses in Manhattan. I made student films.

I learned two things relatively quickly, however — if you wanted to make films, you had, unsurprisingly, to devote much time and passion to the technology of film. You had, also, to devote even more time to making connections and working for years to get a single film made — or somewhat less time, maybe, to produce something low budget fueled by the gas of your empty stomach. Time I might instead be at a desk, in front of a window, imagining, writing, and living in language. So that was how I chose, instead, to devote my creative energies.

And yet it was the mid-1990s now, I was in (or near) Hollywood — and it was the spec screenplay boom years.

When in Hollywood . . .

I returned to writing screenplays.

People familiar with booms of any kind, people familiar with apparently transformative eras — people familiar with Substack, which would be some of you reading this now — know that whole Gold Rush towns spring up to house the new citizens of the new world. Industries develop to feed and profit from the hopes and daring of aspirant souls. In the two thousand aughts, that was blogging. In the 1990s, it was spec screenplay writing.

Let’s Do lunch! Organized, fee-paying, networking lunches all over town. (How I love to network.)

Fast Forward! (Then “Flash” Forward because of some trademark issue.) Costly mass group coaching sessions, with teams and objectives and the whole shebang to guide future Hollywood success stories toward meeting, networking, pitching, cajoling, working that phone to boldly go where so many had tried to go before.

Screenwriting competitions and awards. Win that prize. Attract attention. Make that spec sale. Grab the brass ring and swing, baby.

I actually did fairly okay for someone who hated it all and never did sell a spec script. (How’s that for grading the gradients of success?)

I got appropriately jacked around by any number of bullshit producers. (Really, nobody talks bullshit better, and after a while more obviously, than people calling themselves Hollywood producers. The first prerequisite to being a Hollywood producer is not, actually, as is sometimes said, to call yourself a Hollywood producer or agent. It is to have little to no capacity for self-conscious embarrassment and shame.) My favorite memory of Jay and the Producers regards the very important pitch lunch for which I was calamitously-L.A. traffic late, to find the producer unsurprisingly no doubt long gone. I called and abased myself in apology beyond any instrumental measure. He was so kind and forgiving, I began to wonder. Was nothing I’d heard about these shit-shoveling opportunists actually true? We rescheduled.

And he didn’t show. You might think that he was getting me back, and maybe he was. But I became convinced he hadn’t shown up the first time around either. Which I, of course, couldn’t have known, having been, ahem, so late. There’s a story in there, maybe a movie: we open on an empty outdoor patio table at the Ivy restaurant, on Robertson Boulevard . . .

Where I did “fairly okay” was in the competitions, in which a number of my scripts placed at various levels of recognition, with the highest being my script of What We Were Thinking Of, in two different competitions. It won second place at the Maui (now Hawaii) Writers Conference Screenwriting Competition. (I had it from a source that one judge thought I should have been awarded first place — on such scrawny nails we hang our second-place consolations.) The Maui competition was notable enough to be covered in Variety, where one of the judges, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter himself, was quoted as saying that my screenplay was a “mature, resonant and emotional script that showed the seeds of mastery.”

Something happens when you get written up in Variety. You get attention. Whereas my screenplay-shopping life had previously been confined to narrow, cobblestone lanes of self-abasing, nonentity submission, now I was being contacted unbidden by major studios — their independent production arms, as word was that mine was some kind of arty script not quite right for nationwide rollout. Why, thank you so much for calling, Twentieth Century Searchlight Productions. I’ll get it right in the mail to you. No need? You’ll send a messenger over? Will I still be here in an hour? I think I can manage it.

One of the reasons I can place in memory the late time of the year this all happened is because in those days Julia and I, in imitation of our crazy British cousins, were throwing an annual Beaujolais Nouveau party upon each release of the latest just-off-the-vine vintage. A hundred or more people, half of whom I didn’t know, wandering up and down the stairs of our three-story Venice loft, just behind Abbott Kinney Boulevard, to the beats of the hundred-disc capacity CD changer by which I curated ahead of time the night’s grooves. It was like some Paul Mazursky film — or Hal Ashby’s Shampoo, except Warren Beatty wasn’t shtupping Julie Christie on the pool house floor. (There was no pool house.) That went on for several years until Julia confessed to me, “You know, I don’t really like Beaujolais Nouveau.” Super Tuscan party didn’t carry quite the same spirit of devil may care joie de vivre, and I didn’t really care for all those strange hands fiddling, against the posted rules, with my massive CD changer, so that was the end of that.

But the thing about the Beaujolais Nouveau party that year, soon after the Variety write up, is that many invitees who hadn’t in previous years found themselves able to attend — this time were so able.

And so it goes.

At around the same time, What We Were Thinking Of won the Los Angeles Scriptwriters Network competition, the prize for which, rather than the thousand dollars I netted for the Maui second place, was a professionally staged reading of the screenplay, with Equity actors, at the Beverly Hills Library. It was probably that Sunday afternoon performance that seeded my ideas for the future of the script. To a full house of two hundred people, my cinematically envisioned story, though stage-bound, came vitally, dramatically alive. The actors, particularly those who played the two major roles of David and Charles, were sensational, the reading’s David a moving kaleidoscope of the range of emotions I had written for him, Charles a lion in winter. The actors all expressed their appreciation to me. I expressed mine to them.

Included in the audience that day were my sister, Sharyn, and, still alive, both my parents and Jeff. None of them had ever read any of my writing. My life as a writer was, to them, a phantasm haunting the speech, sometimes, of the family’s youngest child but, in just that way, an unreality in their lives. That day, the writer took corporeal and artistic form before their eyes. Everyone was still mingling amid the congratulations to all, when Jeff approached, after Mom, Dad and Sharyn, his eyes glowing, and placed a hand on my shoulder. “You are a very talented writer,” he said.

Be that moving and affirming confirmation as it may, the truth about competition awarded screenplays, whatever you might presume, is that there is little to no record of their subsequently being produced as films. No correlation whatsoever, except for none at all, and the final judgment about What We Were Thinking Of among the Hollywood literati, despite the script’s wide-ranging locations all over the United States, seemed to be, for the motion picture business, that it was “too talky.”

I lived with that determination for some years, disregarding the “too” element but thinking about the “talky.” The script was indeed dialogue rich, containing multiple characters with strong personalities and distinctive voices who have lots to say. That, I decided, was the makings of a play.

Though I had been a theatergoer for most of my life, having acted and studied drama in high school and college, just as I had fiction and poetry and film, and writing itself, I had never thought to write plays. I had no experience at it. I decided, then, to study playwriting through UCLA Extension. For some years at the time, the Extension instructor in playwriting had been Simon Levy, then and still the producing director at Hollywood’s Fountain Theater, one of the city’s premier small theaters. Simon is also a playwright himself. Among his other plays, Simon is the authorized adapter, by the F. Scott Fitzgerald estate, of the theatrical versions of The Great Gatsby, Tender Is the Night, and The Last Tycoon.

Simon is also an exceptional teacher, praise I don’t easily offer of writing instructors. That didn’t mean — perhaps it necessarily didn’t mean — that my early weeks working with him weren’t frustrating. Draft after draft the same critique came back — “too cinematic.”

What????

Then I had a breakthrough. Sometimes we learn by slowly accumulating the kernels of knowledge and developing the intricacies of craft. Sometimes we experience a flash of insight.

I recognized in just that quick strike of light that what I had been doing until that point was simply transferring the action and scenes from the two-dimensional yet expansive screen to the three-dimensional yet physically confined stage. I was not seeing the theatrical space. I was not reconceiving the drama for the theatrical space, to be expressed through the theatrical space. The fact that characters talk a lot does not make a play theater. “Adaptation” is a misconstrual of the work that must be done when an artist attempts to move a work of art from one medium to another. Adaptation leads to what is almost inevitably pedestrian transfer, a potted, secondhand referral back to the original work and form. What is necessary instead is re-conception, a reimagining from its foundation of what the work of art is and how it functions. This in time I came to do with What We Were Thinking Of.

The play, I happily pronounce, is superior to the screenplay.

In the years since, I have tried without success to get the play fully staged, often letting it languish for long periods after a round of submissions. The responses, when they come, are always positive, often extremely so. But there are always reasons why the production seems not quite right for the particular theater. The cast is not small: no fewer than 10 actors to play 17 roles. The scope presents challenges for a small, black box theater. The subject is large and very pronounced.

Also, finally, cold submission of creative works without networked connections in any artistic form always offers a crap shoot with especially low odds. Writers know this. It is talked about a lot on Substack. This seems especially so, in its own way, with theater, which abides to a degree in its own realm, as both written and performing art. One can find Substack writers representing just about any genre, but there are almost no playwrights and precious few stacks devoted in any manner to theater.

Artists commit themselves to a life in the theater in a unique way, often, when they can, in close connection to theatrical companies and communities. Coming in from the outside without those connections, outside a community and without a commitment to working full time in the theater, isn’t easy.

This leads me to close as I began. I am serializing What We Were Thinking Of here on Homo Vitruvius for you, my readers, to read and to draw attention to it for future productions and readings. If you or someone you know might be interested in arranging a reading or staging a production, I can be contacted at AJayAdlerWriter@outlook.com

Thanks for reading. See you next week for part I of What We Were Thinking Of, “The Words and the Things We Do.”

AJA

Poet. Storyteller. Dramatist. Essayist. Artificer.

Thanks, Brew. Looking forward to your reading it. Would love to hear your thoughts along the way!

Looking forward to reading your play. Great idea.