A note to you, kind readers:

If you are on Substack Notes, you might have seen me comment more than once the past week or so about my working on chapter 6 of Reason for Being in the World, “The Persecution of the Jews,” and that it is taking longer than I anticipated. If you have been reading along, you know that I am writing this “experiment in intellectual and spiritual accounting” — now at book length — in real time, as I publish it in installments on Substack. So, it seems, anticipate the unanticipated.

The effort on the chapter has become daunting, yet it is essential to the thematic purpose of the memoir and necessary at this point in the book’s development, after the chapters on my father’s early life in Ukraine. I persevere accordingly but am delayed in my publishing schedule.

Publishing schedule — there’s a topic. If you’ve been reading me long enough, you know I’ve altered Homo Vitruvius several times already, most recently with the (temporary, I hope) addition of American Samizdat and before that with the elimination of paid posts. (Though I very much wish for, seek, and ask of you, if you can afford it, paid subscriptions.) Now, I think I will alter my approach to the publication schedule. I’ve done that a few times already. Most recently, I’ve tried for twice a week, to accommodate my ambitions for both Homo Vitruvius and American Samizdat. But you see I’ve run into trouble this week, and it occurs to me to clarify again my own needs and purpose as a writer on Substack.

I’m not a blogger. I’m not a magazine. I don’t provide a newsletter service. I am here as a creative writer and thinker to offer intellectually provocative work. That core purpose has motivated previous changes, and it motivates this one. I can’t write creatively and think deeply on schedule, not without fatiguing myself. It comes as it comes, finishes as it finishes. There won’t be set days of the week anymore. I will aim for once per week — still for twice until the election. We’ll see. After Reason for Being in the World is complete in this first, live draft, I’ll begin serializing an already written play. I have particular hopes for it that I’ll announce at the time, and dramatic writing will be something new for you all from me, though not new to me.

All that said, it has been many months since I re-shared an older work from the early Vitruvian days, and this one, “Cool, Man,” my epigrammatic disquisition on the essential nature of cool, goes all the way back to early June last year, when planet Vitruvius was less than two months old. Very few of you will have read it. It offers a plane of thought and feeling a little lighter than the heaviness to come.

Cool?

Cool, Man

In the midst of socially mediating, I came across the observation, from some generational instance younger than my own, that back in the early 90s people of his kind thought the rock band Steely Dan was uncool.

I steadied myself. Easy now.

I read on.

Something to do, I gathered, with creative mainstays Walter Becker and Donald Fagen employing a rotating line up of session musicians with whom to record from album to album rather than a fixed crew of fellow band members. Steely Dan wasn’t, that is to say, a real band. They weren’t, to address the crux of the matter, what a “band” was supposed to be — that was the objection. They weren’t like all the other bands.

Uncool, man.

Cool is as cool does.

Or maybe it’s cool does as cool is.

It is sometimes observed how cool, unlike other historic yet transitory names for the indefinable quality of je nais se quoi, appears to persist – so far, at least – as permanently, qu'est-ce que c'est, “cool.”

Groovy may be, for a time, cool, but cool is not now groovy. (Neither is groovy anymore, long since.) Neither is cool the bomb, or stylin’ (though it styles), or flossin’ (which it would not do in public).

Word.

Cool is not hip, though hip, perennially, fancies itself cool. Hip is self-conscious. Hip strives to be hip. Hip seeks to be joined at the hip with other hip(pies). In another time of my life and another time in the life of New York City, a young lady I very briefly wooed expressed to me the view that people of the New York neighborhood in which I then resided were “tragically hip.” Now, that was a cool phrase.

The tragically hip now reside in a different neighborhood. The cool can reside anywhere.

Cool is singular. Despite what some may say, there is no such thing as a cool crowd. Crowds are not cool.

Cool is not self-conscious. Cool just is. (Did I say that already?)

Cool is not one thing: it has aspects, features.

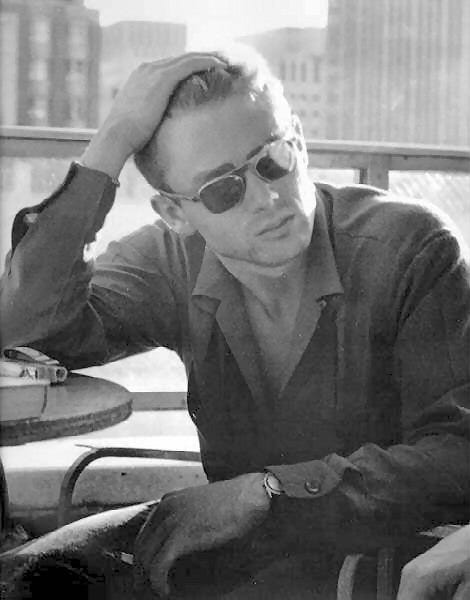

Cool is opaque. It is gazed at but cannot been seen into. It seems to emanate but is also projected upon. It presents a mystery those who witness it seek to solve, without confirmation.

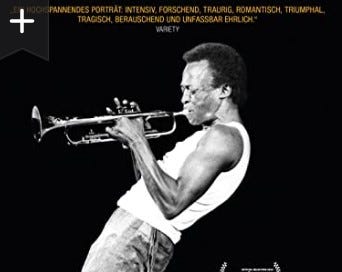

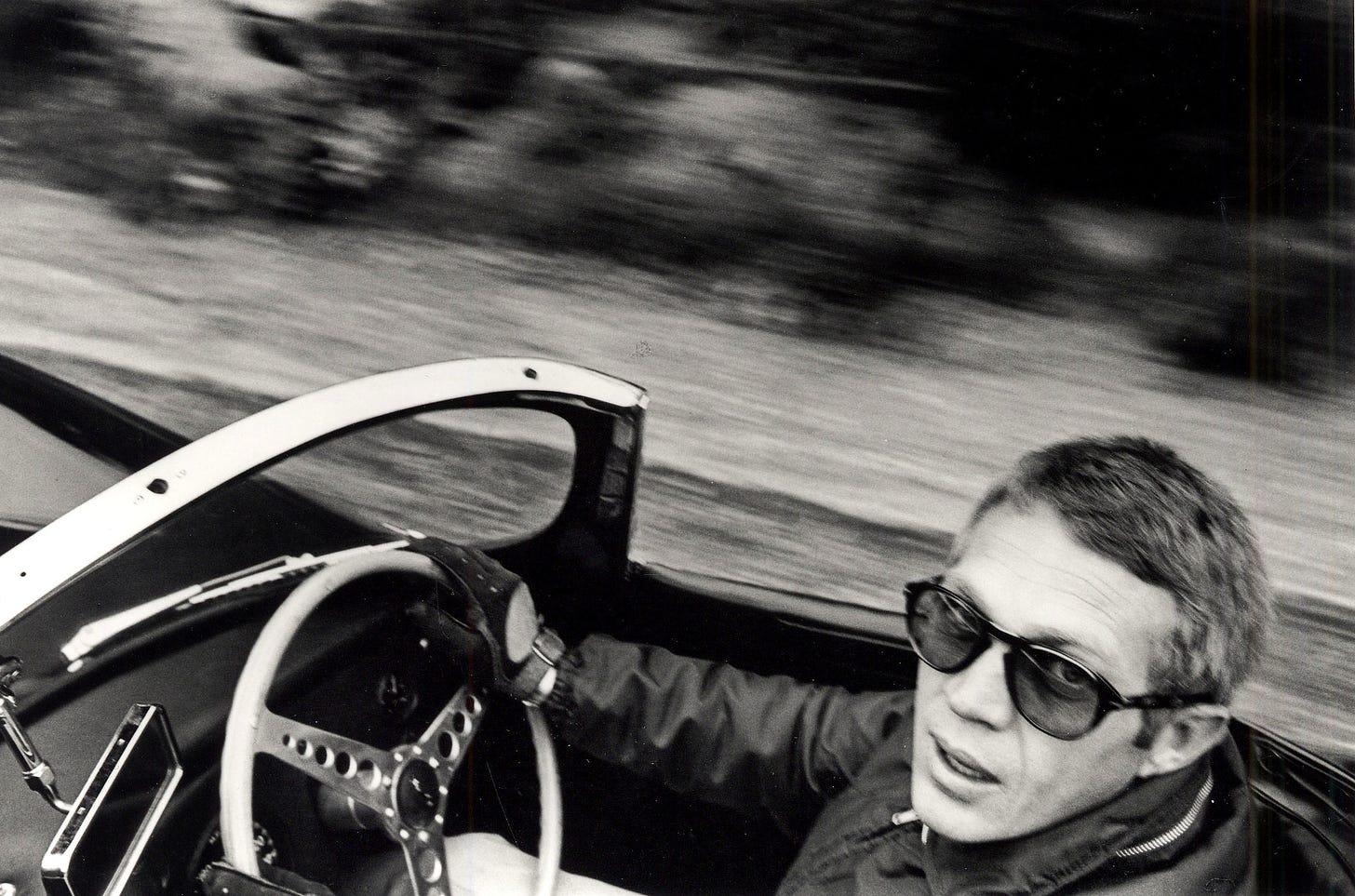

Cool is sexy but it does not seduce. The essence of cool, in its root meaning, is the absence of heat; it is not hot. Hot is open and emotional. It shows itself. Cool remains hidden. It is contained, reserved, detached.

We see roots of cool in the chivalric knight. The knight elicited the regard of others not for his bloodline or his spiritual infusion from God but rather a quality he embodied, an idea of himself he lived by. Would die for. From this arose his radiance.

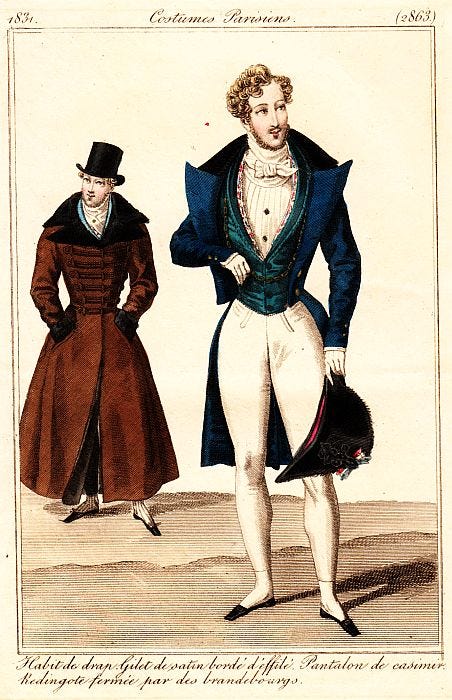

The knight appeared a knight. He wore a form of dress. There was a look. A “look” is a style.

The emergence of the dandy sharpened a focus on style. Baudelaire saw the dandy as a more complex, profound figure than remains in the idea of dandyism since: “The characteristic beauty of the dandy consists above all in that air of coldness that derives from an unshakeable determination not to be moved” (The Painter of Modern Life.)

Style is not “cool.” But cool has style. The dandy might carry a superior or cynical air in his detachment. Neither superiority nor cynicism is cool. Detachment is. To be singular, is to be detached. Cool people do not feel superior to, or cynical about, what others do. It’s just not for them.

Detached is not disconnected. Cool people are implicated in the life around them. This troubles them. They think about the implication. The flaneur, emerging from the dandy, though he appeared idle, did not observe from boredom. He felt interest.

Cool is implicitly political: “The flaneur with his ostentatious composure protests against the production process” (Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project.)

Politics are hot. The politics of cool are outside politics: Cool feels outlaw.

Detached is still. Cool is still. It is introverted.

Cool is not charisma, which is active and extroverted. The charismatic person reaches out, takes hold, in the need to draw others in. Charisma feeds on the other.

Cool people may become “hot,” but their heat emanates from the desire of others reaching toward them. Cool feels consumed by others.

Cool is still, but motion can be cool. Line (stillness in motion) is cool.

Coolness is both person and persona, both or only one. A revealed absence of cool in the person dissolves the cool of the persona. Discovered cool in the person deepens the cool of the persona.

Cool is sincerely ironic: it does not believe in itself but has no other self.

Cool is good looking but good looking is not cool. Cool is interesting. Interesting is interesting.

Cool is androgynous.

Cool smolders: its heat, suppressed, is directed within, attracting heat from others. The attraction of heat toward cool is the draw to danger, the appeal of volatility, in which heat loses its cool.

Cool, combusted, loses its cool.

The cool object – of desire, emulation, aspiration, regard – is a black box. Absorbing light, it remains black.

Cool is what it is, in and of itself, detached, reserved, the reflected mystery of the projection on to it. It is ungraspable, nothing you can put a finger on.

AJA

A new favorite word related to your cool post: sprezzatura

From Wikipedia (not cool, nut not uncool either) : "The term “sprezzatura” first appeared in Baldassare Castiglione's 1528 The Book of the Courtier, where it is defined by the author as 'a certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art and make whatever one does or says appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it'."

"Cool is singular. Despite what some may say, there is no such thing as a cool crowd. Crowds are not cool.

Cool is not self-conscious. Cool just is."

I'm not sure if I really understand what this means. But it's cool. I think.