An Actual Experience of the Virtual Past, (Really)

Extraordinary Ordinary People 4

Time and space can make you feel ten years old again. One way to feel that young, or younger, is through revivified personal memory, in poetry, as I did this past Thursday in “The Fireflies.” Another is through wonder. Time and space are wonder, the surest portals from the demystified everyday world into the estranged quotidian. For ready access to wonder via the imagination, seek no passage less accessible than the photographic image and the sound recording.

Photographic images and sound recordings both function as time machines and space vehicles. So it seems. Most of the time, in most spaces, the time and space are very or relatively recent. Occasionally, though, the passage to the deep hinterlands and times of human activity is great enough to provoke that wonder.

As Wikipedia has it,

Sound recording and reproduction is the electrical, mechanical, electronic, or digital inscription and re-creation of sound waves, such as spoken voice, singing, instrumental music, or sound effects. The two main classes of sound recording technology are analog recording and digital recording. [Emphasis added]

About photography, Wikipedia tells us,

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. . ..

. . . .

Typically, a lens is used to focus the light reflected or emitted from objects into a real image on the light-sensitive surface inside a camera during a timed exposure. With an electronic image sensor, this produces an electrical charge at each pixel, which is electronically processed and stored in a digital image file for subsequent display or processing. The result with photographic emulsion is an invisible latent image, which is later chemically "developed" into a visible image. [Emphasis added]

When we consider why we take the photographic image as real, as somehow an objective piece of the real past, preserved for our attention now, in the object’s future – in contrast to even the most accurate representational realism in painting – it is because the image partakes in the reality of the light that was in contact with the photographed object: the light that reaches our eyes, streamed from the object it departed, to be held in latency in the emulsion or digitized state for future streaming to us. Almost a suspended animation, like an ancient body mummified in ice. It is not the person. The person is dead. But it is . . . something, some material expression of the person that was.

So it is with sound recording, captured and retained – inscribed in latency – and then released in play to reach our ears.

None of this is so of even the most accurate representational painting, whatever its purpose to record what the artist sees. It is even less so of a Bach cantata performed on original (or recreated original) instruments.

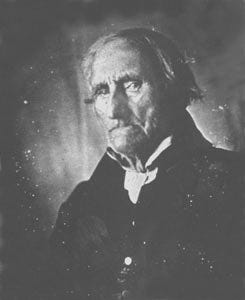

Below you see a photograph of Conrad Heyer, one of a very few people commonly presented as the earliest born in time to have been photographed alive. The image is a c. 1852 daguerreotype. As with almost all contenders for the designation, Heyer’s birth year has not been definitely established. Both 1749 and 1753 are claimed. He died in 1856. The son of German immigrants, Heyer was a Massachusetts Bay farmer. In 1776, he married Mary Weber. They had ten children.

At the Journal of the American Revolution, you can read a remarkable and meticulously researched assessment of the claims about Heyer, including strong argument, based on the evidence, against the common claim that he was among those who crossed the Delaware with Washington.

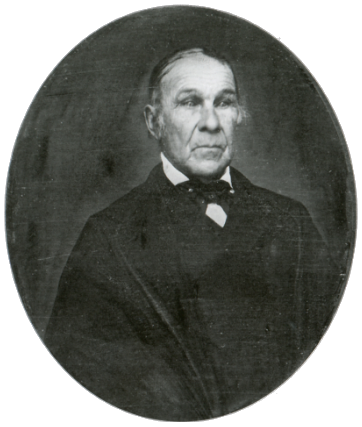

These days, a stronger claim for the honor is made for (the unrelated) John Adams, also a veteran of the Revolutionary War (though unlike Heyer, he never applied for a government pension). He is known to have enlisted just after the April 19, 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord. Unlike Heyer, Adams’s “date of birth is confirmed by the New England Historic Genealogical Society's Vital Records of Worcester, Massachusetts [documented at Ancestry].” The 1845 photo was commemorated as having been taken on his 100th birthday.

A third contender is Ceasar, the last enslaved person to be officially freed in New York State, in 1841, when all forms of slavery became illegal in the state. He spent his life living in Bethlehem, New York, outliving three generations of slave masters. It is claimed that he was born in 1737, but there is no corroborating documentary evidence as such. The photograph was taken in 1851. Ceasar died the following year.

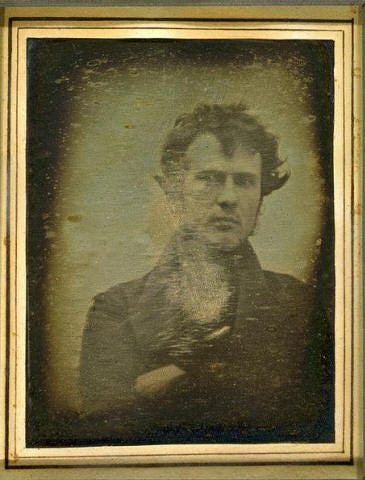

While there are several earlier claimants, none survive: this daguerreotype, below, by Robert Cornelius is the “earliest surviving photographic portrait image of a human ever produced.” It dates to October or November 1839. Cornelius took it of himself. It is a self-portrait. It is the first selfie.

Maybe only because of his youth compared to our earlier centenarians, his face seems so – modern. So real.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.