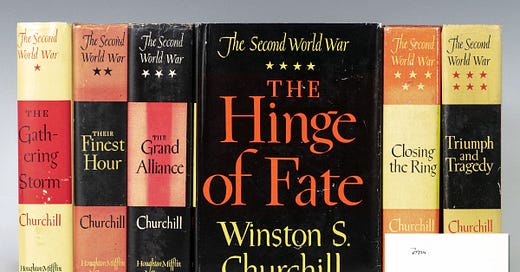

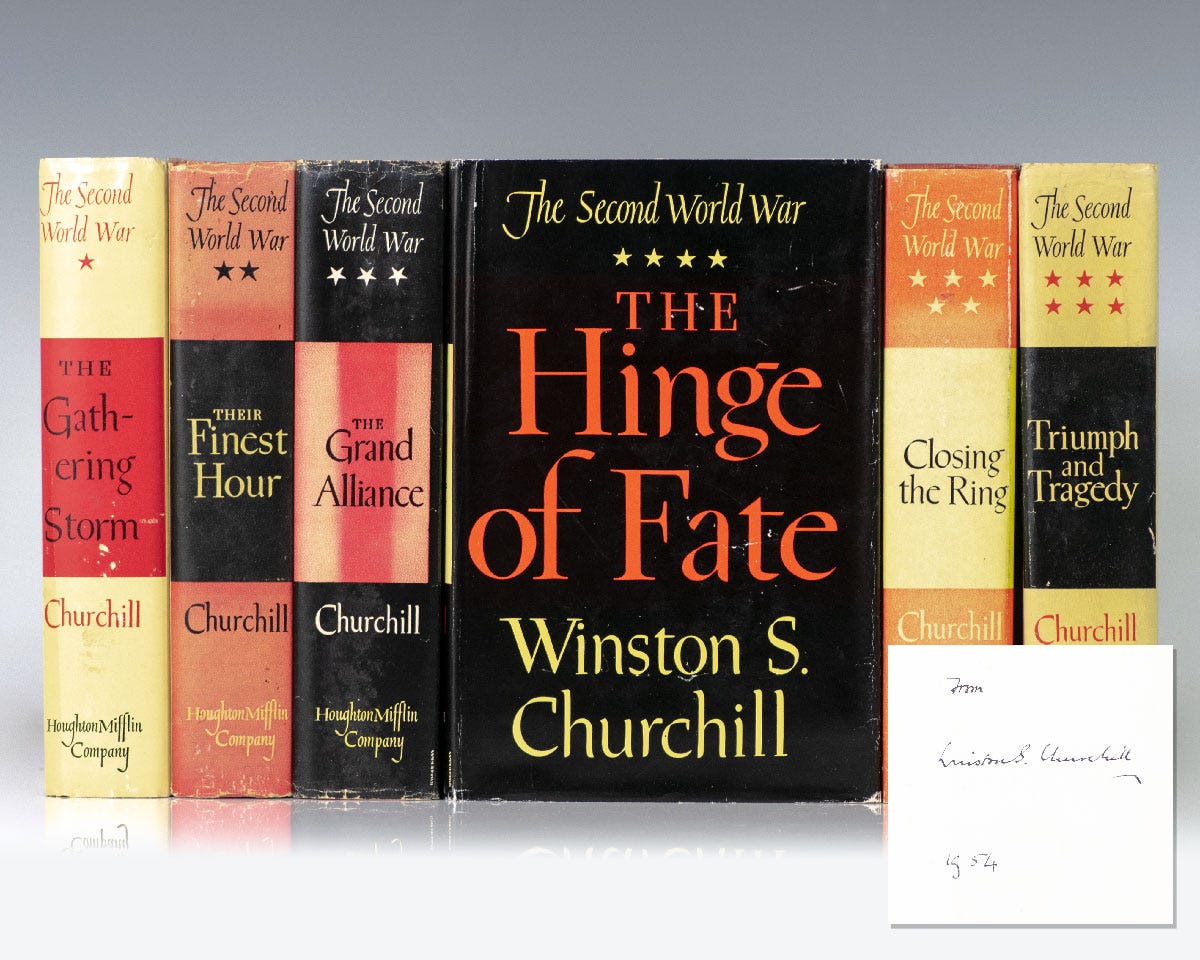

American Samizdat: The Hinge of Fate

This November, the United States and the world will turn on it.

Every day for the first four months of Donald Trump’s administration, I reminded all I could on Twitter that through his continued ownership of the Trump International Hotel in Washington D.C. — through which he daily earned income from those, foreign and domestic, doing business with the United States government — Trump was violating the Constitution’s emoluments clause. Remember that quaint principle of honest government we heard so much of at the time? Who speaks of it now?

That was the beginning, on day 1 of his presidency, of Trump’s law breaking, without being held to account, day after day as head of state and government of the United States of America. That was how quickly he began to undermine the rule of law, how …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.