Wherein I develop themes from three of the selections in “A Reader’s Review 2,” on the New York Intellectuals, Guernica Magazine, and Ann Manov’s review of Lauren Oyler on Bookforum.

Last month’s Closer Look essay was “The Code.”

Agonies of the Agon

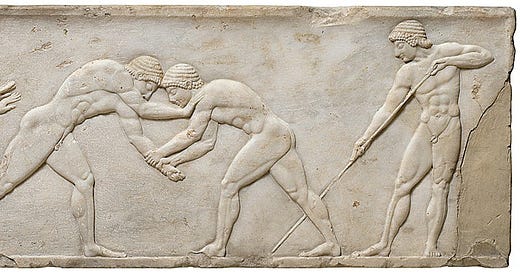

The ancient Greeks famously seeded the garden of civilization with, among other botanicals, philosophy, democracy, rhetoric, natural science, drama, epic poetry, a full universe of symbolic and personified mythology – and the Olympics. The Olympics extend farther back in time, perhaps, than all of those other contributions but the epic poetry, as song. The ancient Olympics – gatherings for sport, as we would think it – were sites of contest and competition. The Greek word for it is “agon,” from which English derives protagonist and antagonist, primary figures of drama in contest – in conflict – with each other.

The hardship of the agon, with its test of endurance and will, the possibility of loss, and the physical or mental pain inherent in the contest produces another derivative term: agony. Declared the voiceover introduction to the long running U.S. ABC television sports program The Wide World of Sports, it showed us “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.”

There was at Olympia, Greece, site of the earliest games, even a statue of the personified spirit of Agon.

We read it from Classicist Nigel B. Crowther that

the Olympic Games were not actually the Olympic Games in ancient Greece, . . . since they were not diversions or amusements, but the subject of real competition with everything it implies.

Competition (or the agon) permeated the society of the Greeks. According to the distinguished Classicist Bernard Knox, "this competitive spirit had its roots in the disparate nature of their political organization, the cities all vying for territory, for predominance."

When we think of agonism in our lives, in the life of the world – the contest over all the things humans contest, the conflicts that ensue – we can consider the Greeks both to have been expressing throughout their culture a value — an esteemed ideal — and embodying in their lives what they believed to be their natural selves.

When I contemplate the spirit of the agon in my own life, I see several influences. I’ve mentioned in the past my love of sports cars, from which follows fast driving. I pursued this activity in the most amateurish fashion, as most fast drivers do, whatever their fantasies, by speeding on public roadways. Occasionally, my youthful testosterone bumping up against its like enclosed on the road in another five or six-geared machine revving its motor, I engaged in impromptu one-on-one races. The most memorable took place between the Verrazano Narrows Bridge crossing of New York’s Belt Parkway in Brooklyn and the Rockaway Boulevard exit to JFK airport in Queens, a distance of nearly 25 miles.

My Datsun 280ZX became pitted in natural eruption of male aggression against a Mazda RX7, a competition in those days that probably struck both drivers as ordained by the vehicles. I never saw the other, male driver’s face. The parkway traffic, midday, flowed in its usual New York density, though freely enough for such a race, of endless weaving in and out, to transpire. We reached speeds, when possible, of 90-100 MPH. The race revealed us both well, amateurishly skilled. That this behavior was utterly and recklessly irresponsible goes without saying, but there, I’ve said it. We might have caused horrendous damage and loss of life. I was then 28 years old, at the peak of my and my startup employer’s business success, and the closing comment to every cocktail-infused business strategizing session at some bar each night, from someone, was “Fuck ‘em if they can’t take a joke.”

This is part of my point: I was young, male, and steaming ahead in full bore competitiveness.

In such a race, there is no finish line known to both contestants, so each imagines his own. For me, it was that Rockaway Boulevard exit: I was due back at the office. We exchanged the lead many times. The thrill of such racing is in the contingency of the course, with sudden unmapped obstacles (other, oblivious cars and drivers) moment by moment appearing in your way. It is video game life before video games, but you can really die. If I was in the lead when I exited the parkway, in my mind I would have won. Not far from the exit, I was indeed in the lead, and at that point, from recent maneuvering, in the middle lane. The other driver was speeding up toward me in the left lane. If he passed me, I would have no time to regain the lead before exiting. I had time and space to cut into the left lane ahead of him. But it was close: would he be able to slow in time, and what if not?

I let him pass.

Agony of defeat.

I have attributed this behavior so far to a generic young male’s aggressive hunger for contest. But I did not think myself a mere generic young male and, like anyone else, I wasn’t. The twenty-eight-year-old me, born of the particular circumstances of my life, acted out his new-born assertiveness in response to the hurts of his youth. As I wrote in the essay referenced above, I was a painfully shy and sensitive child, who often recoiled from the wounds the world inflicted on him, in the same manner as my father. My father’s wounds were shaped in the form of parental abandonment, World War I, the Russian Civil War, and pogroms, whereas I, his youngest child, decades later, just had my feelings hurt a lot, but what did five-year-old me know of the horrors of world history? I reacted against my hurts as my father did, in upsurges of anger, occasionally rage, against whatever or whoever it was that stood to wound me.

So when my young businessman self acted out his assertiveness, it wasn’t simply “young male” fulfilling his genetically programmed, hormonally boosted role. It was “me,” saying I wasn’t going to take this anymore. I would stand up for myself, and from what I could increasingly see in the world around me, there was much to stand up against.

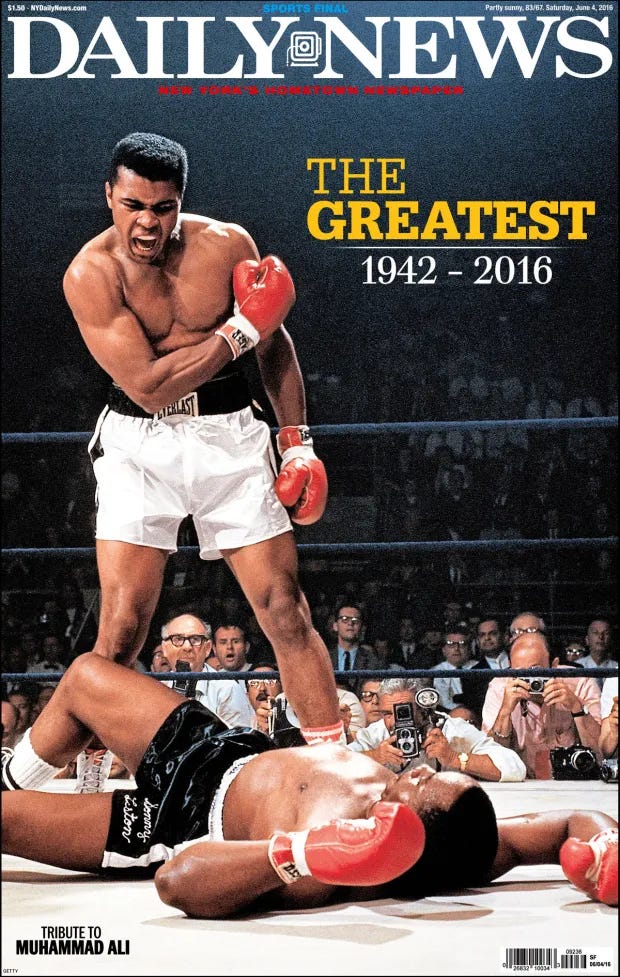

The process of learning self-defense and then assertion was gradual. When still that timid child, I attended a Catskill Mountains summer boxing camp run by Al Silvani, the former trainer of middle weight champ Rocky Graziano. I learned well enough for an 8-year-old. I won the junior division competition. Boxing became a part of my life, not as a sport I pursued, though I could now fight for myself, but as an anger-channeling interest. When I first entered into psychotherapy, at 17, after my devastating freakout on LSD, my therapist was struck by the identification I had established with Muhammad Ali. I hadn’t considered it. But of course, Ali served as perfect stand in for anyone who felt “the world,” some powerful aggregate of forces, stood against him, working to prevent him from being himself, unmolested and unrestrained.

Among my other sporting interests, boxing remained a passionate attachment all through Ali’s career and the sport’s second golden age of the 1970s and 80s. I saw the major fights of all the greatest champions, especially those that matched them against each other. I appreciated the artistry of the “sweet science,” but when I attended fights with my male peers, we rose with the blood in our veins and cheered with fists that punched the air when our favorite rallied a fierce bombardment of punches upon the toppling tree of his opponent. I sat alone at a Shea Stadium closed circuit telecast and shouted unrestrainedly for Sugar Ray Leonard despite the gladiatorial munus roar of the overwhelmingly Latino crowd standing around me for Roberto “Manos de Piedra” Duran.

There was more going on than sweet science.

Earlier and far greater than my business bravado and sporting barbarism were my creative and intellectual drives, developing as they were under the many influences of New York City’s spirited 1960s and 70s social and cultural conflict zone. These influences included, prominently, the largely Jewish New York Intellectuals, who had forged their early careers in the social and political tumult of the Depression era. In Thursday’s Review, I wrote of this diverse group how, according to Ronnie A. Grinberg in Write like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals, they developed as a “testosterone-driven literary circle.” They exalted, she writes, “a masculinity centered on strength, toughness, and virility,” which became a characteristic of the intellectual life of New York. Writes Benjamin Balint, reviewing Grinberg’s book, these were “a group … who ‘prized verbal combativeness, polemical aggression, and an unflinching style of argumentation.’”

But however much one might tie a profile of these writers to a group psychological analysis and an anatomy of a singular ethnic group’s historico-cultural development, the contest of ideas — to the death even — looms as old as the first idea and over all intellectual history.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.