A Map of the Time of the Mind

Recs and Revs: The Magellanic Diaries 5

When I determined to write a novel about Ferdinand Magellan’s 1519 expedition, I set as one of my preparatory tasks to develop a sense of what European consciousness might have been like at that period in history, more particularly Spanish and Portuguese. I thought it an essential task. To write a historical novel without consideration of this subject seemed a certain course to the inauthentic. How did the experience of consciousness differ from that of the modern, based on ideas of the self, the body and mind, and the ideas there were in the world infusing that idea of self. It wasn’t a matter of discovering the truth but rather of achieving some reasonable sense of the possible that could translate into persuasive inner lives.

What does it mean to live a life in space, within vastly different spaces, from housing to rural and cityscapes to knowledge and conceptions of earthly space? What does it mean to live a life in time with a different understanding of time?

This wasn’t a subject I imagined investigating directly. I thought, rather, to be alert to the question as I researched more concrete matters and to absorb that sense of consciousness more naturally – almost just as I might have had I lived in that time. (Ah, were it only so, traveling consciously backward in time to travel bodily back in time.) That’s how I proceeded. Research on the novel has advanced aided by bountiful sums of serendipity. Information came my way by the way, looking for something else, all the time. Information and ideas of which I had no inkling at all to seek out arrived through vague links, passing references, and footnotes to open new and unexpected plot lines and vistas for the story.

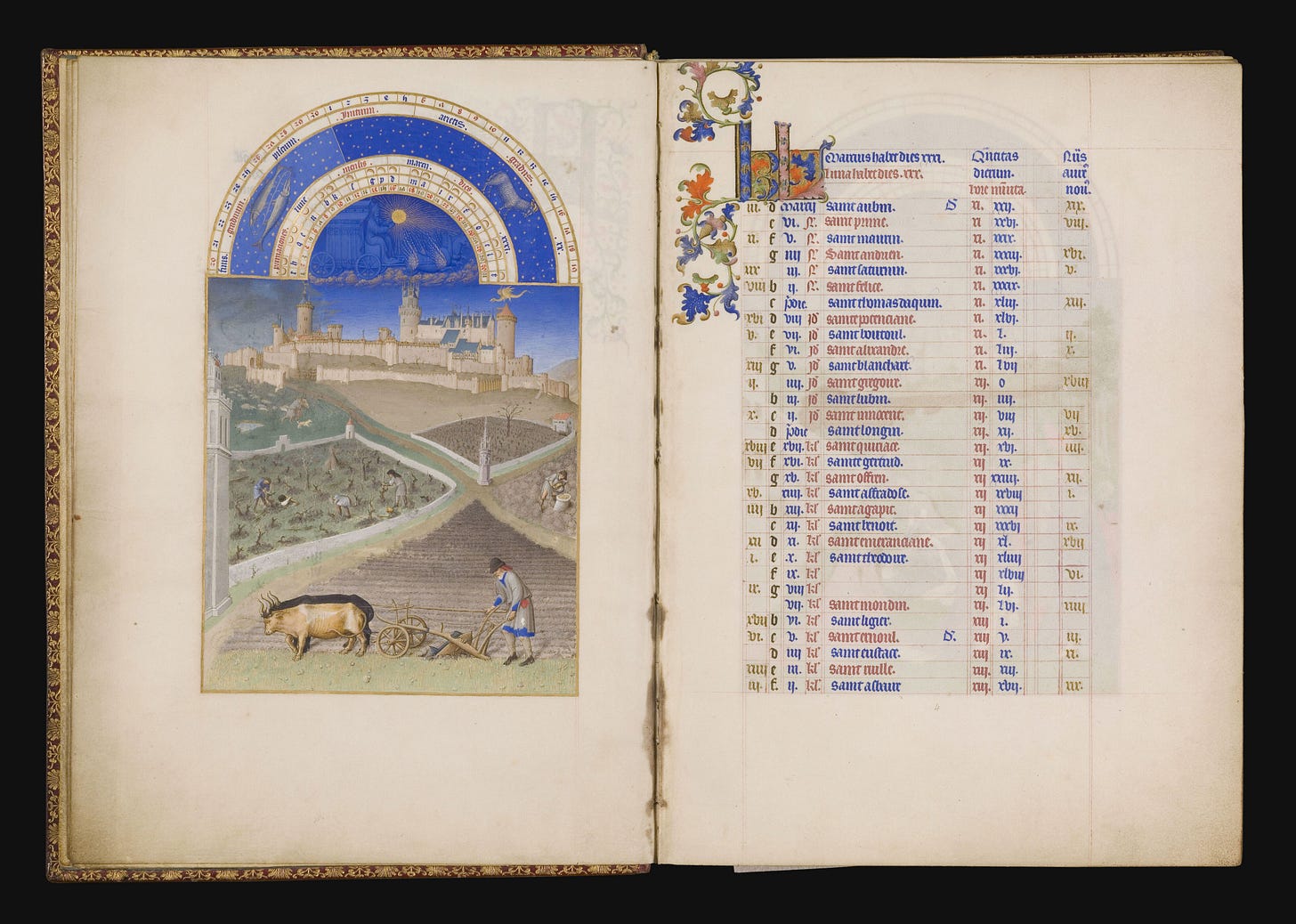

One of so many is the following: the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry), brother of King Charles V. This codex is what is known as a book of hours, traditionally a collection of prayers, also an illuminated manuscript created for the duke by the brothers Herman, Johan and Paul Limbourg between about 1414-1416. It is considered the supreme existent example of such a book. Beyond its obvious beauty, on 206 leaves of parchment, including 66 illustrated miniatures and 65 small ones, I was drawn into vital historic envisionings of time, spatially represented on the leaves of the book. I was led to this understanding by reading Jason Farago, a 2023 Pulitzer finalist for his New York Times art criticism.

The Très Riches Heures isn’t only a breviary, however. Any book of hours opens also with a calendar. But this one, a Julian calendar, is more like an almanac, spelling out solar movements and feast days.

Farago explored the book’s representations as part of a Times series he helped develop.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Homo Vitruvius by A. Jay Adler to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.